Teaching and Mentorship

My teaching and mentorship encompasses traditional settings at US-based universities and progressive experiential settings notably as the Lead of the Leaders of Africa Institute’s flagship Research Methods Program. Learn more about my approach and select courses.

Approach to Teaching

and Learning

I believe that good teaching cultivates a learner’s perception, voice, and skill. Perception is important because it involves critical inquiry and often self-reflection that helps us uncover things that are not easily seen or personally experienced. This is achieved in part by offering a diverse learning space with diverse learners, experiences, and materials that are inclusive including amplifying presently under-representative voices. Voice emerges as the avenue through which learners express themselves through communication and activist persuasion. Skill underlies both perception and voice with an emphasis on using cutting-edge and traditional tools and techniques to pursue inquiry and co-creation, including rigorous research methods.

In practice, my teaching has three parts: foundations, inquiry, and co-creation. I want to ensure that all learners have strong foundations, which involves understanding the history, present state, and projected future movements in the field. This is important because it allows the learner to observe both continuity and change in the field while also situating themselves as active participants in the present and shaping the future of the field. Inquiry is the process of investigation, interrogation, and self-reflection with the purpose of generating original insights. I emphasize asking and justifying interesting questions, identifying gaps in our contemporary knowledge, designing creative methods to generate new knowledge and data, and doing so through diverse assignments, exercises, and projects. On the basis of inquiry, I encourage my learners to co-create social innovations that translate our ideas and improve the human condition. I believe that we should ensure that the fruits of our knowledge production are shared equitably.

Select Course

Themes

Comparative Politics

Freedom House, an organization that tracks regime types across the world, emphasized in their most recent report (2019) that only 9% of the total sub-Saharan African population (over 1.1 billion) lives in a “free” country. There is a mix of regimes represented across the continent. Beneath these broad regime-level generalizations are diverse societies with a diverse set of historical and contemporary experiences. This course offers an introductory exploration of these experiences. In this context, we will explore three themes:

Development Challenges and State-Society Relations

“Africa” is often depicted in the news and by aid agencies as underdeveloped, highly socio-economically unequal, unstable and prone to violence, wracked by ethnic division and conflict, and dominated by political leaders with long tenures who refuse to give up power. How accurate are these depictions? We will interrogate these narratives by investigating some of the development challenges facing African societies (e.g., resource distribution and health), as well as considering the relationship between the state, political processes, and development challenges. In addition to examining development-related concerns, we will discuss where to find and how to analyze data related to economic development and state attributes.

Regime Change and Stability

African countries have experienced periods of both regime change and stability. Freedom House’s 2019 report points out that some of the major declines in freedom over the past ten years have occurred in African countries, such as Burundi, Mali, Central African Republic, Tanzania, and Benin. More short-term declines have been observed in Benin, Mozambique, Tanzania, Burkina Faso, and Guinea. For instance, although regular elections are common in African countries, there is a great variation in the quality of these elections. Authoritarian regimes have been able to adapt to the realities of holding elections. We will examine this adaptation. We will also investigate important institutions that comprise regimes, with attention to election quality, executive power, human rights, and conflict. And, we will consider the role that international actors (e.g., international institutions and major world powers) play in shaping regime change and stability.

Public Opinion and Data in Political Science Inquiry

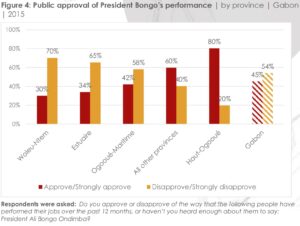

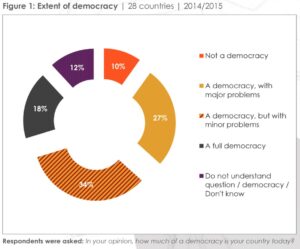

In this course, you will gain data analysis skills alongside content knowledge. We will spend time exploring start-of-the-art data sources available to researchers of African politics, mainly the public opinion data from Afrobarometer, the World Bank Development Indicators, and Freedom House. In particular, our use of Afrobarometer data will allow us to discuss the diverse experiences of African citizens and “let people have a say.” Throughout the course, you will strengthen your ability to find and evaluate relevant data, conduct some basic analyses, and present your findings.

Most countries around the world hold elections, but the quality of these elections differs greatly. In authoritarian and democratic regimes there are attempts to shape the electoral playing field in ways that can harm representation and accountability. This course examines several dimensions of election quality ranging from voter registration to campaigns to the reporting of results in countries across the globe. In the context of exploring election quality, the course will also investigate the nature of campaigns and election results in both authoritarian and democratic countries. In particular, we will consider campaign dynamics and strategy given institutional and regime constraints in a diverse set of countries across the globe. We will explore four themes:

The Importance of Elections in Deepening Democratic Governance

A fundamental aspect of democracy is regular elections. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights embraces several international principles including free and fair elections, due process, and basic freedoms, such as the freedom of association and expression. In particular, almost all countries hold elections, and most countries do so regularly. However, not all elections meet the minimal international standards for elections.

Election Quality and Efforts to Improve Elections

Freedom House, an organization that tracks regime type across the world, emphasized in their most recent report (2019) that only 4%, 11%, and 39% of citizens live in what is classified as “free” country in the Middle East and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Asia-Pacific regions respectively. Some countries in these regions experience some of the most egregious violations of human rights at election time and election malpractice. At the same time, there are international and domestic efforts to improve election quality. We will investigate the effectiveness of these efforts.

Differences in Campaigns and Activism across Countries and Diffusion of Practices

We will also look at mobilization efforts by political parties and aspirants in campaigns, as well as activism by civil society to improve elections and democratic behavior. In addition, where elections become associated with political violence, we will consider the causes of political violence and examine efforts to attenuate the violence.

Data in Political Science Inquiry

The cutting edge of political science includes qualitative and quantitative data inquiry. It is important not to be afraid of quantitative political science, while at the same time interrogating the appropriateness of our most respected measurements. We will explore some of the most useful datasets and quantitative models employed for interpreting election quality, political institutions, and election results.

The Freedom House organization recently suggested that there has been a 13-year decline in the level of democracy globally. Countries that were seemingly on a more democratic trajectory, such as Benin and Zambia, have experienced a deliberate move toward authoritarianism. In Myanmar, the hope for a new democratic dispensation is now greatly diminished. Finally, among countries in the West, democratic values and practices are being questioned by so-called populist leaders and associated parties. This course examines the foundations of democracy and explores the challenges to democratic rule with an emphasis on developing countries, such as countries at a political crossroads and new democracies. The course will also consider the rise of “populism” among countries in the West. Finally, the course will consider the global, national, and local factors that shape discontent with democracy, as well as interrogate whether discontent necessarily leads to a resurgence of authoritarianism. The course will emphasize four themes relevant to the study of democratic politics and our present dispensation:

Democratization and Challenges to Democracy

Many commentators and academics have pointed to the resurgence of authoritarian rule and efforts by select states, political parties, and leaders to impart a more authoritarian ethos. We will integrate the nature of the purported democratic erosion among democratic countries and the prospects for democratization among authoritarian countries. In particular, we will interrogate the nature of populism and its purported rise. We will also discuss the arguments for and against democracy.

Global and Divergent Forms of Erosion

If democratic erosion is taking place, how does it differ cross-nationally? We will look at trends in the challenges to democracy at a domestic, regional, and global level to determine whether there are similarities and differences. For instance, does skepticism with democracy have the same causes and manifest itself the same way across countries? We want to explore a nuanced perspective on the sources of discontent.

Opportunities for Resistance and its Limits

Citizens, civil society, and some political actors have resisted – for a variety of reasons – democratic erosion. Most visibly, they have engaged in peaceful and violent protests. In some cases, persistent resistance has blunted or slowed creeping authoritarianism, while in other cases resistance has been met by violent repression. We examine the different strategies aimed at confronting democratic deficits and assess their relative efficacy.

Data in Political Science Inquiry

The cutting edge of political science includes qualitative and quantitative data inquiry. It is important not to be afraid of quantitative political science, while at the same time interrogating the appropriateness of our most respected measurements. We will explore some of the most useful datasets employed for interpreting regime type and public opinion. We will consider how our measurements may be influencing our understanding of democratic deficits.

We are witnessing a global pandemic, economic turmoil, and the ascendancy of political parties openly embracing autocratic politics and ethnonationalism among other pressing concerns. The Global Comparative Politics course challenges you to step out of your comfort zone and consider the political experiences within different polities across the globe. By studying politics in other countries – other than our own – we can gain valuable lessons applicable to our global context and obtain a broader perspective on political arrangements, behavior, and values. This semester’s course emphasizes four themes relevant to the study of global politics and our present dispensation:

Challenges to Democracy and the Manifestation of Authoritarian Populism

The United States is not the only country that has seen the rise of more overt forms of extremism and demagoguery. Democracy experts have raised alarm about the leadership in Poland, Hungary, India, and the Philippines embracing increasingly autocratic and exclusionary policies. We interrogate the nature of the purported democratic erosion among democratic countries and the prospects for democratization among authoritarian countries. In addition, the course explores the rise of authoritarian populist movements in different countries.

Institutional Challenges

Disenchantment with the political process may in part be attributed to poorly designed institutions, or institutions (formal and informal) that advantage certain groups of people. We explore the extent to which formal and informal institutions contribute to perverse political outcomes, such as violence, lack of trust, and disenfranchisement.

The Century of Developing Countries

The world order is experiencing significant change. With large (and young) populations and markets, India and China are rapidly developing and asserting their place as leaders on the global stage. They are not alone. We examine what development in previously less developed areas of the globe means for domestic politics in developing and developed countries and the world economy.

Data in Political Science Inquiry

The cutting edge of political science includes qualitative and quantitative data inquiry. It is important not to be afraid of quantitative political science, while at the same time interrogating the appropriateness of our most respected measurements. We explore some of the most useful datasets employed for interpreting regime type, public opinion, and economic development.

International Relations and Development

There is a proliferation of international organizations covering domains from economic regulation to security to political norms. These international organizations have varying aspirations ranging from facilitating transactions between states to transnational political unification and federation. However, not everyone has desired extensive international cooperation. Some political movements and citizen protest movements have questioned the benefits of international cooperation and succeeded in spurring withdrawals from institutions. No examples are as clear as the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union and the United States’ pursuit of protectionist policies in recent years. Further, in response to the global pandemic, countries have turned inward although the threat of the COVID-19 virus demands global cooperation. Against this backdrop, this semester’s course emphasizes three themes relevant to the study of international organizations and our present dispensation:

The Promise of Cooperation Considered

The course considers how and why international organizations have proliferated and evolved in their influence on political, economic, and security outcomes. This involves examining the basis for cooperation or (lack thereof). We consider the confluence of factors that move countries towards closer integration and how incentives of cooperation shape patterns worldwide. The course also considers the forces that may incentivize critiques of international organizations and the failure of cooperation to materialize or deepen in situations where cooperation already exists.

Institution-Building, Revision, and Destruction

Many international organizations are well-known including the United Nations, African Union, and European Union while others may be lesser known including the Economic Community of West African States, Mercosur, and Association of Southeast Asian Nations. The course examines the institutional arrangements in existence and what they portend for policy and outcomes. The course approaches the study comparatively by examining the similarities and differences between international organizations and considering the interaction between domestic politics and international organizations, particularly for organizations with political (e.g., democracy and governance) and distributional (e.g., trade) consequences. In addition to organizations comprised of states, the course examines the role of international non-governmental organizations.

The View from the Global South

We often emphasize the importance of major world powers in shaping international organizations and international organizations in which major powers participate. At the same time, international organizations and associations, such as the African Union, Mercosur, and Association of Southeast Asian Nations, have become increasingly important in facilitating integration and managing cooperation. We examine international organizations of countries in the Global South and how the Global South interacts with international organizations outside of their immediate neighborhood.

The world recently celebrated the seventieth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The UDHR enshrines many important rights, including freedom of expression, freedom from arbitrary arrest and torture, non-discrimination, access to social security, and the ability of citizens to choose their government – to name a few. The UDHR is just one form that international law takes. There are many other sanctioned treaties, charters, and protocols that comprise international law, such as the European Convention on Human Rights and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. This seminar explores these critical documents and the associated institutions (e.g., the International Criminal Court) that comprise international law. We will address one of the major questions in international relations: does international law shape international and domestic behavior and outcomes? We will also consider a wide range of case studies that involve international conflict and security and domestic politics. In particular, we will explore four themes:

Advancements in International and Human Rights Law

The development of international law has a long history that reflects the reaction to major global events, including the World Wars. However, advancements in international law have not been uniform across all domains. We will examine the causes of this lack of uniformity and what it tells us about the future of the development of international law.

Relationship between International Law and Institutional Development

Accompanying the development of international law are critical institutions that help with the application and enforcement of human rights law and norms. These institutions include the International Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice, as well as the United Nations and its organs. We will examine why and how institutions are created and developed over time.

Understanding the Effects of International Law

The major question we consider in studying international law is whether it influences the behavior of actors (e.g., states, organizations, groups, militias – among others). We will investigate the conditions under which international law and institutions have a measurable influence on human rights outcomes and when they fail to achieve the results we expect.

Data in Political Science Inquiry

The cutting edge of political science includes qualitative and quantitative data inquiry. It is important not to be afraid of quantitative political science, while at the same time interrogating the appropriateness of our most respected measurements. We will explore some of the most useful datasets and quantitative models employed for interpreting international law, institutions, and causal effects.

The UN Development Program (UNDP)’s most recent 2016 report states “human development is all about people—expanding their freedoms, enlarging their choices, enhancing their capabilities and improving their opportunities. It is a process as well as an outcome. Economic growth and income are means to human development but not ends in themselves—because it is the richness of people’s lives, not the richness of economies, that ultimately is valuable to people.” To this effect, the UNDP estimates that many countries face challenges stemming from underdevelopment. Using the general measure of the Human Development Index, it is clear that development varies across the globe, with significant underdevelopment in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East. Nevertheless, the level of development has increased in most world regions, but to varying degrees and rates over time. What factors shape the global variation?

This course considers the challenges of development, including theories of development, development policy, and other influences on the various aspects of development. Freedom House, an organization that tracks regime type across the world, emphasized in their most recent report (2018) that only 5%, 11%, and 38% of citizens live in what is classified as “free” country in the Middle East and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Asia-Pacific regions respectively.

This course examines how regime characteristics and political processes can and do influence the level of development and development policy. Is it necessary to have representative institutions to further development? Does development, in turn, influence the political environment, including leading to democratization and democratic consolidation? The course considers how development shapes political life and how political life shapes the development process and outcomes.

The course will focus on three themes: (1) development challenges and state-society relations; (2) political influence on development; and (3) metrics of development and data in political science inquiry.

Research Methods

The Advanced Research Design course explores advanced research design techniques and supports advanced studies in quantitative methods. All research begins with a quality research design. The course surveys the important assumptions underlying research pursuits and emphasizes the importance of crafting an interesting and well-framed research question that seeks to build general knowledge on a given topic. The course also explores how research questions may be answered using a mix of methodological approaches — qualitative and quantitative. This challenges the notion that either qualitative or quantitative methods approaches are superior. Rather, each set of approaches can be leveraged to answer a research question.

The Data Science and Quantitative Methods course explores basic and advanced quantitative methods techniques. In particular, the emphasis will be on understanding the structure of quantitative data. Using real development and survey data, the course will explore how to visually represent data and calculate descriptive statistics that will help in making decisions about the data, its representation, and analysis, such as decisions about aggregation and creating indexes. The course will also cover using regression and logistic regression models to test hypotheses, alongside a discussion about dealing with common issues with regression. Finally, there will be an emphasis on how to interpret and explain quantitative results to academic and policy audiences. All of the work for the course will be completed using R with the R Studio wrapper – a free and advanced statistical software, which can be used in any quantitative methods setting.

Data is increasingly important for making informed decisions and solving global challenges. The expansion of available data and tools, such as artificial intelligence, allows us to build advanced analytical models. It also means we must craft new and innovative ways to communicate data so that we maximize social impact by engaging local and global leaders. The Data and Design for Development course accelerates data visualization projects, which distill data for broad audiences and advance social impact. The program offers instruction in data visualization platforms including Tableau, Microsoft Power BI, Datawrapper, and Flourish alongside mentorship to build original data experiences.

The Advanced Survey Design course explores survey methods and analysis. One of the most common sources of data is survey responses, and many of you have expressed an interest in conducting a survey. In the past, many of you have served as enumerators for survey-based projects as well. This course prepares you to conduct your own survey research, data gathering, and analysis feasibly with a limited research budget. In particular, the course provides a rigorous and advanced discussion of survey design and implementation. In the latter part of the course, you will begin to use R to conduct quantitative analyses of survey data. The course will also offer an opportunity to fine-tune your research design and skills as you pursue original research.

Media, Communications, and Social Entrepreneurship

Podcasting and documentary filmmaking are some of the fastest-growing digital journalism mediums. Podcasts and documentaries can reach a global and local audience and stimulate learning and conversations on important themes. Podcasts and documentaries are increasingly becoming a medium for social impact and activism, as well as entertainment and demonstrating expertise. You will learn the skill of audio and video storytelling by creating, editing, and publishing multimedia projects that include scripted stories and unscripted interview and discussion programs. We will also examine revenue-generating models as well as the ethical challenges of advertising, sponsorship, and branding. By the end of the program, you will be able to launch audio podcasts and produce documentaries for organizations, such as news sites, non-profits, or for your personal use. Beyond getting a broad understanding of podcasting and documentary filmmaking, you will learn important journalism skills, including sound design and non-linear editing software.

Research is increasingly being used to inform social innovation in many fields spanning public health to energy access. The translation of research involves developing products, services, and policies that can have a social impact. It also means developing financially sustainable approaches that allow for growth and equitable access. In this program, we examine research-inspired social innovations, practice human-centered design approaches to product, service, and policy development, craft financial models for sustainable growth, and build organizational structures to massify impact.